A Full Bird Exclusive

September 12, 201809/12/2018 From the Right

"Price gouging" laws don't protect you during a crisis. They cause shortages.

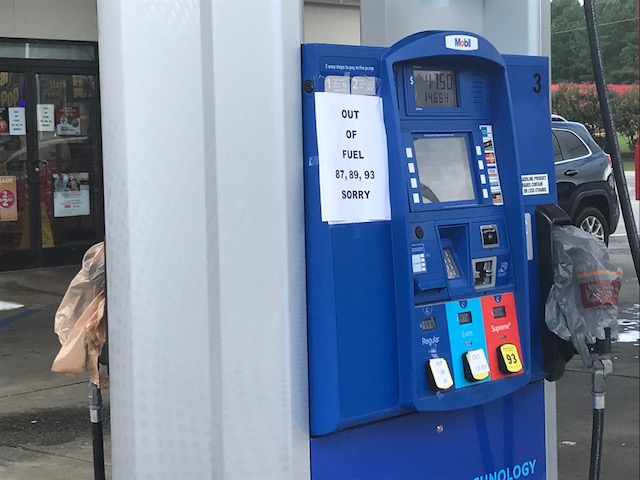

A picture I took of an unnamed gas station in the Raleigh area days before Florence arrived

Yesterday an understandable panic set into much of North Carolina and the surrounding states as Hurricane Florence threatened to arrive later in the week. Driving home in Raleigh, the highway was so backed up that I decided to get off a couple miles before my exit and take backroads. Bad move. It took me another 45 minutes to go those two miles because of a mix of evacuating coastal residents and locals scrounging for provisions.

I took note that every gas station I passed was packed with lines filling their parking lots. "There are still a couple days," I thought. "I'll get gas at a calmer moment tomorrow."

"Out of fuel. Sorry."

As a writer, I have some flexibility on what time I can buy my gas, so I went out at around 10 a.m. the next day. As I pulled in I saw the price had barely budged from the day before. "Whoa, nice!" I thought, having expected it to be maybe 50 cents higher based on what I'd seen the day before.

But then I saw something that I wasn't as happy about. That picture at the top of this post was one I snapped as I pulled up to the pumps. All the pumps had bags over them and a sign let me know that there was no gas to be had. But why? In basic supply and demand economics, if there is huge demand, won't prices go up to prevent shortages and also to send a signal to suppliers that more gas is needed urgently? Yes, but we do not operate under basic economics during a crisis. We are more working under the "misinformed compassion" model. Our "price gouging" laws are now in full effect since Gov. Cooper declared a state of emergency. Here is Attorney General Josh Stein making that clear.

“My office is here to protect North Carolinians from scams and frauds,” said Attorney General Josh Stein. “That is true all the time – but especially during severe weather. It is against the law to charge an excessive price during a state of emergency. If you see a business taking advantage of this storm, either before or after it hits, please let my office know so we can hold them accountable.”

But this wasn't my only experience with basic economics as I prepared for the hurricane. I went to the Food Lion near my house the night before. As I walked in, I saw a sign saying, "4 waters per customer only." Now I realize they meant four PALLETS of bottled water.

As I was buying milk (I'm fine with tap water so I didn't bother with all the bottled stuff), an employee walked out of the stock room with two pallets of water and helped put them in a man's cart. Apparently there had been no more in the aisle so he had to go back to get them. Then a woman standing nearby asked him, "Can you grab me some too?"

"No," he said laughing. "I just gave the last of it to him."

Whoa. They had no more water even after limiting people to four pallets of water. Now, I really hope all these people aren't going to need even one pallet of water to get through the hurricane. They likely bought that amount to feel more secure and prepared as they hunkered down.

What if these stores were not under threat from the state's attorney general though and could just let their prices rise as demand rises? With the opportunity to move a massively inflated number of units at equally inflated prices, wouldn't Food Lion, and many other water-dispensing vendors, immediately demand huge shipments of water to be delivered? Wouldn't also the guy buying four pallets of water decide maybe he only needed two, easing some of the upward pressure on demand?

Well, that's how it works in every other sector of the economy, so we don't really even have to speculate. Economists tell us this every time there is a major crisis. Search any journal of economics, or Forbes Magazine, the CATO Institute, or even our great North Carolina think tank the John Locke Foundation, and you will see research on this. You may also find articles like this one from the LA Times though, titled, "Memo to economists defending price gouging in a disaster: It's still wrong morally and economically" written post Hurricane Harvey. Here's a little sample from that piece.

"Where does that leave a low-income mother with, say, three children needing to be hydrated? She might need a couple of dozen bottles, for which the price has now risen to $168 from $24. Throw in that, with the electricity out, she might not even have access to cash at an ATM. She might very well value that water at $7 a bottle, in principle. But that won’t matter, because she can’t afford it. This is why the public typically views price gougers as creeps."

The author creates a scenario grounded in reality, citing the reality of water reaching $7 a bottle reported in the aftermath of Harvey. But the alternative to their admittedly sad and possible story is not abundant $1 bottles of water; it's no water on the shelves at all.

In fact, it is likely to make the water more expensive on the black markets that emerge in these circumstances than it would have been at the store. People who by 30 pallets at the artificially low cost contribute to the shortage, but sometimes they become the new "store." And because they are not regulated and law has often broken down, they are free to charge the real value. If it were priced at $7 at the store, which had established re-supply arrangements, it may be more like $10 at the makeshift corner stand with the cardboard sign, because when they're out, they're really out.

So, while the motivation for price gouging laws is compassion, it is more about "seeming" compassionate than being compassionate (to make brief use of our state motto). If you see a high price for water or gas, and a line of people waiting patiently with cash in hand, don't call Josh Stein. Thank them for making goods available that are clearly needed by many people.